Flashbacks

A Ghost Town, Memories, and Real Magic

Great High Mountain

When I lived in Knoxville, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was a 45-minute drive from my apartment. I worked at a television network all week and soon as 5PM on a Friday hit, I loaded my huskies into my Subaru forester, and we drove east to the park with wolves’ heads hanging out the window and the soundtrack to Cold Mountain blasting.

Weekends were for hiking, exploring, and immersing myself in mountain culture. I loved every aspect of it. I loved the outdoor sports and camping and wildlife. I loved the history and music that birthed from those hollers, all the sounds and stories.

I grew up in the eastern mountains, but the defunct factory town I was raised in was a Superfund site. My town killed its mountain. Poisoned it into a hellscape of brown mudrock and dead trees. Finding myself grown, amongst the larger, greener, wilder mountains of the southern Appalachians felt like healing.

I don’t know if I’ll ever experience anything like my early twenties in East Tennessee again. The feeling of my adult life just starting. A new (to me) car, money in my bank account, two gorgeous huskies, health insurance, 20+ miles of hiking a weekend, jumping off waterfalls, dulcimer concerts with warm handpies by the river…

My healthy young body with working joints, still thinking I had a lifetime ahead to hike the AT or fall in love or see the Tibetan Horse Racing Festival.

It was paradise. Not the park, but the possibility of more time.

More time. That’s the one thing we all worship.

Spend enough time around the Park and you hear the gossip at visitor centers and trailheads. I only lived in Tennessee for two summers, but I was lucky enough to hear some rumors about special events in the park, usually not advertised.

One that caught my attention was this lore about a special congregations of fireflies. That at certain times, at certain elevations, the fireflies did something magical. They synced up. A lot of them.

They didn’t twinkle like distant stars. They synchronized their flashes, all turning on and off simultaneously like god was flicking a light swtch in the middle of the wilderness. And it wasn’t a few of them. It wasn’t like how they started to flash in my childhood backyard, a few disparate souls adding some whimsy to the view from the porch. No, this was an army.

This was more fireflies meeting than I’d ever seen in any place in my life. It was a convention. A few minutes after dark, the silent, slow-motion strobe lights started. Their soundtrack the sound of the river and the distant hoots of owls. It sounded so magical. It sounded sacred.

I had to see it.

It’s a rare event, and has grown increasingly popular with the rise of social media, a boom and curse to all our National Parks. Today if you want to see it, you need to apply for a 4-hour viewing permit through a lottery held by the National Park Service or travel to remote parts of Southeast Asia. The Big Sync only occurs for a week, once a year, and only in a few places around the world. But I happened to live an hour away from it once, so I made it my personal mission to see this live show.

The Ghosts of Elkmont

The magic fireflies happened near the Little River, amongst an abandoned resort town called Elkmont. Elkmont used to be Cherokee land, home to thousands of people who called it home for generations before the Trail of Tears sent them to reservations and a logging company took down paradise and put up a parking lot.

Once the majestic hardwoods were felled and the land deemed “useless” the logging company left and land was sold to people who wanted cabins away from the city easily reachable through the logging roads. In under 80 years the land went from Cherokee holy land, to getting raped of all resources and left barren, and then sold off to wealthy tycoons from Knoxville.

By 1912 Elkmont had multiple cabins and two hotels for the wealthy immigrants. While real Americans from North Carolina were watching their grandchildren grow up in poverty on Oklahoma reservations.

When I saw them, men, women and children, moving along thro' the valley towards the far west, . . . I could not help but think that some fearful retribution would yet come upon us from this much impugned race. The scene seemed to be more like a distempered dream, or something worthy of the dark ages than like a present reality; but it was too true.

-The Diary of Lieutenant John Phelps, June 22, 1838 - On watching Cherokee walking away from home for the last time. In less than a hundred years there would be hotels where they lived, prayed, and thrived for generations. This is called progress to some people.

We’re not responsible for that, those of us reading this today. That doesn’t mean we’re immune to the consequences, nor should we run from the gravity. Shameful history isn’t about guilt. It’s about lessons. And if we pretend they never happened, we lose the wisdom so many people suffered for. It’s not only childish, it’s tacky.

When the National Park took over the property the 1930s, the government bought out all but the wealthiest cabin owners and their property. The remaining rich owners got grandfathered into a couple more decades, living in the National Park for their resort summer vacations until, eventually, by the 1980s - the once opulent woodland resort of Titanic-Era boom wealth finally died out. A quarter century after the last residents of Elkmont had left and all that remained was abandoned cabins, 23-year-old Jenna was standing in the ghost town for the first time.

When I walked around those cabins in 2006, they were all still standing but locked and boarded up. I remember them looking blueish gray in the dusk light, the way old barns do when they aren’t painted and left to the elements. I remember looking at them like shipwrecks with somber awe.

Now most of those cabins are gone, taken down between 2016-2022. I’m sure all the small ones I used to walk around are nothing but stone chimneys and slab rock porches. I read that a few have been restored for modern park guests, in an area called “Daisy Town” and there’s a very popular campground near it as well. But the Elkmont of hotels and white money is long gone. It looks more like it did for the Cherokee when I was there, the empty cabins settling into the tropical slant of time. It felt like justice.

Back when I saw the lights, there was no lottery. There was a pair of buses. You parked at a specific lot closer to the Gatlinburg side of the park and got in line, first come, first boarded. It cost me nothing.

All us tourists and scientists and local nature nerds got into our places and were driven a short ten minute trip up winding roads to the ghost town. The ranger leading our bus explained the rules. This was not a time to blast your boombox or take flash photography. This was not for screaming kids and barking dogs. This was basically a pilgrimage.

We all had our backpacks with snacks and sweatshirts and water bottles and flashlights, but few of us had the red light setting on our torches. So the ranger handed me a few pieces of red cellophane and a rubber band, just like she handed to anyone else without. Only red light was permitted, as anything too bright would throw off the choreography. I slid it over my headlamp and turned it on to see the spooky red glow. It felt like that scene in Jurassic Park when Timmy puts on the night vision goggles, but without the looming threat of death by Kaiju.

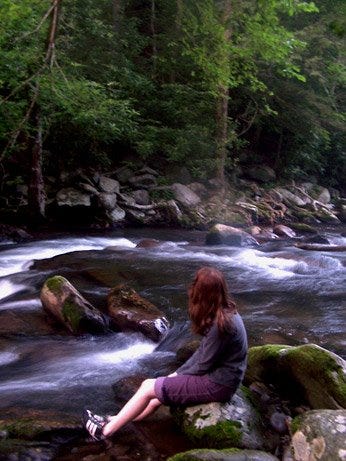

Everyone unloaded from their busses and most tourists only walked as far as they had to so they could set up their folding chairs away from the bus’s exhaust fumes. But me and my roommate walked out to the river and set ourselves up on the rocks. I found a picture I took before sunset of my roommate, waiting by the Little River for the big show.

When darkness fell you could feel the energy hum. It was the feeling of hundreds of people’s anticipation. It felt like before a thunderstorm (also a real possibility in early June in Tennessee).

Slowly the first fireflies came out. A small flash in the distance here or there and then right in front of your face. It would slowly gain more friends, swirling just a few feet above the ground. By full dark there were so many fireflies near the river congregating, it felt like old magic. Something out of a fantasy novel, which is all I ever wanted from my one human life. Had a unicorn emerged from a copse of trees or a kelpie cried out from the river, I wouldn’t have even blinked. We’d all be watching the same thing together.

Soon the fireflies started to flash together in small groups. Like a small clique of friends doing the wave in their corner of the stadium, trying like hell to make it catch on. Soon entire corners of Elkmont were flashing together. Within moments, every firefly, thousands upon thousands, started to flash together.

I can still see it.

The world went from pitch black to yellow wonder in seconds, illuminating the trees and duff and water in neon light before disappearing for a few seconds, and lighting it up again. It’s impossible to explain how my heart stopped. It’s wild to know this is something I actually witnessed. I’ve never seen the Northern Lights. I never owned a passport. But I got to see this. And I wouldn’t trade it in for winning The Amazing Race or millions of dollars. Our lives aren’t stamps and currency. They’re memories.

In the moment I became instantly nostalgic, a bad habit of mine since I was a child. I was the only 9-year-old I knew telling myself to savor the moment because I’d be dead soon. Even if I made it to my early 100s, that was soon.

I don’t remember when I learned about death? It was just something I always knew. But even as a child I never woke up thinking I would survive the day. I still don’t. Which may explain why I have chosen the life I have.

This thinking persists. I can’t even say to friends “See ya at the party next week!” Because I am well aware that anything could unsubscribe me from life at any second, so I always say “That’s the plan!” because it is. The plan is to survive till next week, because I want to stick around. But I never want to live in the mind of someone who expects it. Imagine what you’ll put off if you think you have more time? Terrifying.

I will never forget those fireflies. A species in decline here in the United States because they need deep ground litter to breed in, something too many people rake up from their perfect lawns and wonder why they don’t see fireflies like they used to as kids. You need a place a little wilder, a little higher, a little rougher. You need a place with moving water, a canopy of trees, and the desire to sit and take in the show.

I feel very lucky to have landed on a little mountain farm, where every night in June I can sit on my deck, in the glow of citronella torchlight, and watch the fireflies come out and fill the farm with that same magic I can tap into from nearly 20 years ago. Not as intense, because nothing is as intense as a 23-year-old living on her own for the first time far from home. But I still feel the wonder. I still see the shuttered cabins’ outline in the red glow of a hundred covered flashlights. I still remember that I’m here for a short time, like everyone else who watched them before me.

Elkmont comes back to me all the time. The flashbacks of the flashes. The way I didn’t understand myself, my place in the world, or who I was yet but knew enough about impermanence and holiness to understand this might be the place my last thoughts take me before I die. To a little river beside stolen land, where all sorts of people and lives and stories happened since and how so many of them may have felt that same feeling of home, regardless of how they got there or why. The kids of loggers in 1900. The last remaining resort tenants in the 1970s. The ancestors of the Cherokee, and me… all sharing one memory over centuries.

We’re just as fleeting. Our future is a prayer, not a promise. But while we remain among the light, take a moment to say thank you. Not to god or nature or bugs, but to time. It’s all we got.

As more of my neighbors and I give up our lawns and let some wild places return to our yards, we are seeing more fireflies, although not in the numbers I remember from my childhood. Thank you for sharing this amazing memory. I’ll think of this now whenever I see fireflies.

What an amazing experience, I had no idea they did this!